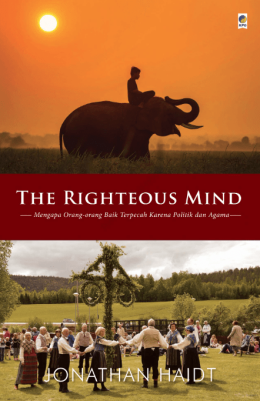

The Righteous Mind – Web Tải Sách Miễn Phí Ebooks PDF

Giới thiệu & trích đoạn ebook

Where Does Morality Come From?

I’m going to tell you a brief story. Pause after you read it and decide whether the people in the story did anything morally wrong.

A family’s dog was killed by a car in front of their house. They had heard that dog meat was delicious, so they cut up the dog’s body and cooked it and ate it for dinner. Nobody saw them do this.

If you are like most of the well-educated people in my studies, you felt an initial flash of disgust, but you hesitated before saying the family had done anything morally wrong. After all, the dog was dead already, so they didn’t hurt it, right? And it was their dog, so they had a right to do what they wanted with the carcass, no? If I pushed you to make a judgment, odds are you’d give me a nuanced answer, something like “Well, I think it’s disgusting, and I think they should have just buried the dog, but I wouldn’t say it was morally wrong.”

OK, here’s a more challenging story:

A man goes to the supermarket once a week and buys a chicken. But before cooking the chicken, he has sexual intercourse with it. Then he cooks it and eats it.

Once again, no harm, nobody else knows, and, like the dog-eating family, it involves a kind of recycling that is—as some of my research subjects pointed out—an efficient use of natural resources. But now the disgust is so much stronger, and the action just seems so … degrading. Does that make it wrong? If you’re an educated and politically liberal Westerner, you’ll probably give another nuanced answer, one that acknowledges the man’s right to do what he wants, as long as he doesn’t hurt anyone.

But if you are not a liberal or libertarian Westerner, you probably think it’s wrong—morally wrong—for someone to have sex with a chicken carcass and then eat it. For you, as for most people on the planet, morality is broad. Some actions are wrong even though they don’t hurt anyone. Understanding the simple fact that morality differs around the world, and even within societies, is the first step toward understanding your righteous mind. The next step is to understand where these many moralities came from in the first place.

THE ORIGIN OF MORALITY (TAKE 1)

I studied philosophy in college, hoping to figure out the meaning of life. After watching too many Woody Allen movies, I had the mistaken impression that philosophy would be of some help.1 But I had taken some psychology courses too, and I loved them, so I chose to continue. In 1987 I was admitted to the graduate program in psychology at the University of Pennsylvania. I had a vague plan to conduct experiments on the psychology of humor. I thought it might be fun to do research that let me hang out in comedy clubs.

A week after arriving in Philadelphia, I sat down to talk with Jonathan Baron, a professor who studies how people think and make decisions. With my (minimal) background in philosophy, we had a good discussion about ethics. Baron asked me point-blank: “Is moral thinking any different from other kinds of thinking?” I said that thinking about moral issues (such as whether abortion is wrong) seemed different from thinking about other kinds of questions (such as where to go to dinner tonight), because of the much greater need to provide reasons justifying your moral judgments to other people. Baron responded enthusiastically, and we talked about some ways one might compare moral thinking to other kinds of thinking in the lab. The next day, on the basis of little more than a feeling of encouragement, I asked him to be my advisor and I set off to study moral psychology.

In 1987, moral psychology was a part of developmental psychology. Researchers focused on questions such as how children develop in their thinking about rules, especially rules of fairness. The big question behind this research was: How do children come to know right from wrong? Where does morality come from?

There are two obvious answers to this question: nature or nurture. If you pick nature, then you’re a nativist. You believe that moral knowledge is native in our minds. It comes preloaded, perhaps in our God-inscribed hearts (as the Bible says), or in our evolved moral emotions (as Darwin argued).2

But if you believe that moral knowledge comes from nurture, then you are an empiricist.3 You believe that children are more or less blank slates at birth (as John Locke said).4 If morality varies around the world and across the centuries, then how could it be innate? Whatever morals we have as adults must have been learned during childhood from our own experience, which includes adults telling us what’s right and wrong. (Empirical means “from observation or experience.”)

But this is a false choice, and in 1987 moral psychology was mostly focused on a third answer: rationalism, which says that kids figure out morality for themselves. Jean Piaget, the greatest developmental psychologist of all time, began his career as a zoologist studying mollusks and insects in his native Switzerland. He was fascinated by the stages that animals went through as they transformed themselves from, say, caterpillars to butterflies. Later, when his attention turned to children, he brought with him this interest in stages of development. Piaget wanted to know how the extraordinary sophistication of adult thinking (a cognitive butterfly) emerges from the limited abilities of young children (lowly caterpillars).

Piaget focused on the kinds of errors kids make. For example, he’d put water into two identical drinking glasses and ask kids to tell him if the glasses held the same amount of water. (Yes.) Then he’d pour the contents of one of the glasses into a tall skinny glass and ask the child to compare the new glass to the one that had not been touched. Kids younger than six or seven usually say that the tall skinny glass now holds more water, because the level is higher. They don’t understand that the total volume of water is conserved when it moves from glass to glass. He also found that it’s pointless for adults to explain the conservation of volume to kids. The kids won’t get it until they reach an age (and cognitive stage) when their minds are ready for it. And when they are ready, they’ll figure it out for themselves just by playing with cups of water.

In other words, the understanding of the conservation of volume wasn’t innate, and it wasn’t learned from adults. Kids figure it out for themselves, but only when their minds are ready and they are given the right kinds of experiences.

Piaget applied this cognitive-developmental approach to the study of children’s moral thinking as well.5 He got down on his hands and knees to play marbles with children, and sometimes he deliberately broke rules and played dumb. The children then responded to his mistakes, and in so doing, they revealed their growing ability to respect rules, change rules, take turns, and resolve disputes. This growing knowledge came in orderly stages, as children’s cognitive abilities matured.

Piaget argued that children’s understanding of morality is like their understanding of those water glasses: we can’t say that it is innate, and we can’t say that kids learn it directly from adults.6 It is, rather, self-constructed as kids play with other kids. Taking turns in a game is like pouring water back and forth between glasses. No matter how often you do it with three-year-olds, they’re just not ready to get the concept of fairness,7 any more than they can understand the conservation of volume. But once they’ve reached the age of five or six, then playing games, having arguments, and working things out together will help them learn about fairness far more effectively than any sermon from adults.

This is the essence of psychological rationalism: We grow into our rationality as caterpillars grow into butterflies. If the caterpillar eats enough leaves, it will (eventually) grow wings. And if the child gets enough experiences of turn taking, sharing, and playground justice, it will (eventually) become a moral creature, able to use its rational capacities to solve ever harder problems. Rationality is our nature, and good moral reasoning is the end point of development.

Rationalism has a long and complex history in philosophy. In this book I’ll use the word rationalist to describe anyone who believes that reasoning is the most important and reliable way to obtain moral knowledge.8

Sách liên quan

Donate Ủng hộ chúng tớ 1 ly cafe

Nhằm duy trì website tồn tại lâu dài và phát triển, nếu bạn yêu thích Taiebooks.com có thể ủng hộ chúng tớ 1 ly cafe để thêm động lực nha.

Bạn cần biết thêm lý do để ủng hộ Taiebooks.com ?

- Website cần duy trì tên miền, máy chủ lưu trữ dữ liệu tải ebook và đọc online miễn phí.

- Đơn giản bạn là một người yêu mến sách & Taiebooks.com.